| Taken from "Cricket in the Shadows" by Brian Freestone and reproduced here with his kind permission. Transcribed by Sarah Gilbert |

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

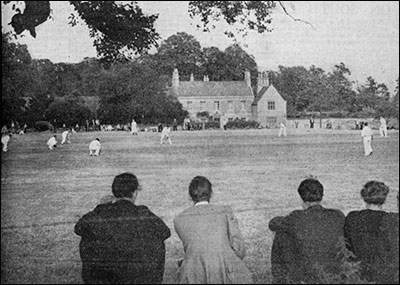

The cricket ground at Burton Latimer lies just off the A6 main

The north side of the ground was open to the fields which led the eye away to the sharp embankment of the The Hall opposite was a mysterious place in which we could imagine all sorts of strange happenings but its grey stone walls kept its secrets to itself. None of us were ever invited into this different world. Its encroaching woods, thick and black, were impenetrable even to the most daring of Opposite the Hall was and still is the official main gate. The ground is prevented from spilling onto the A6 by a light grey stone wall which is capped by thin blue slate. On the special “County Match” day, when payment was demanded, when pocket money was something in the region of 3d (1.5p) a week, unofficial access could be gained by ducking and weaving through the undergrowth of various spinneys on the west side, to emerge on to the ground and whistle unconcernedly, hands sunk deep into pockets, as if one had every legitimate right to be there. We were masters in this skill, devious and colourless as spies in a cold war. As one approached the ground from the west a strange view of the match formed since a bank obscured all of the game except for the heads and shoulders of the players. The resulting picture was reminiscent of targets jerking spastically along at the rickety target range of the town annual fair. A small stream bi-passed the ground on its north side and was said to feed some obscured fishponds in the Hall grounds. It was a mildly picturesque ground but to us it seemed yet again that everything was in its place, God could not have chosen a better setting. It was another step up from the “Rec.” Although the ground sloped downwards the square was very flat and of a reasonable standard. The same could not be said of the outfield, uneven as a rucked carpet. Treacherous as a cakewalk, it spread upwards and outwards away from the square on two of its sides. Long tufts of wet grass often slowed up intended fours. They were as efficient as sand on a fire, as effective as the best fieldsman. And home cricketers were not slow to take advantage of this characteristic. An opposition batsman, having hit the ball fiercesomely towards the boundary would set off smartly for the first run, the fielder being in rapid pursuit of the already decelerating ball. In very wet conditions its path would be traced by the spiral fling of water droplets. The fielder, having gained on the ball, would appear to have lost it in the long and wet grass but all the time he was keeping a close watch on the position of the batsman for whom the temptation of runs was too great. He would set off for another run. At precisely that moment and, as if obeying an electrical impulse, the fielder would discover the ball miraculously (below his feet all the time) and wing it into the wicket keeper leaving the batsman stranded in a self-made slough of humility in the middle of the pitch - and laid bare for all to see. The fielder would be congratulated for his cunning, the spectators would laugh unkindly and the batsman would slink off to the pavilion wishing perhaps that he could join the rabbits in their warm and friendly warren underneath the pavilion. At least there he would be safe from the wrath of his captain and the riling wit of the rest of the team. It was such an obvious trick but it was surprising how effective it was on so many occasions. Many batsmen, having tried for that extra run have lived to rue their gullibility. One of the highlights of the cricket season at Burton Latimer’s ground was the evening Knockout Tournament, a twenty over game between teams made up of men from the town’s factories, shops, societies and religious institutions. For some, this was their one and only brief flirtation with the game since childhood. At that time people gave up sport at a much earlier age than today’s competitors, expectations were much lower. (Many more men smoked cigarettes in those days too, and one is tempted to make a connection.) Brief rivalries were renewed and men took on a fierce loyalty to their own team even though they had been called in as last minute replacements. Several played in work clothes for they had no other; some played in their every day shoes reeking of leather from the factory floor, not a sight witnessed in today’s atmosphere of plenty when it is often a struggle to find a space in changing rooms so cluttered up are they with “coffin” kitbags. But the enthusiasms of these men were admirable, unquestioned and unquestioning and humour was never far from the surface. Each one gloried in taking part in these cricketing dramas as we had done earlier in our “Rec” enthusiasms. There were rules for qualification. Each team member had to have been born in the town, live in it or work in it. There was no room for outsiders. This meant that everyone knew everyone else and the atmosphere was thick with the good humoured cries of men. All was in good fun and it also brought much needed finance to the club, the main reason for the existence of such a tournament. Teams joined in wholeheartedly whatever their individual differences. Even the “Chapel” team, strongly anti-alcohol, would temporarily shelve its convictions and play against “Pub” teams. This was another natural step in our development begun so enthusiastically at “The Rec”. The reasons behind the tournament were admirable, but man being man in his obscene search for personalised and selfish glory, for empty triumph, soon began to tinker with the rules and make inroads into this innocent set up. In the early fifties the premise of having to win at all costs began to show its ugly façade with the insidious practise of importing good players from the surrounding towns. In no time at all this destroyed all the primitive innocence of the tournament and introduced a semi-professional air when one was not needed. We wanted to reserve that sort of thing for our own precious dreams. The “imported” men were usually able to dismiss our efforts with a blatant disregard. Rapidly the tournament lost its point. The team for which I played owed its allegiances to the Baptist Chapel whose influence was serious and strong. We were considered something of a joke team, for even in the early fifties the Chapel’s disciplined views on life were already somewhat out of fashion. And we didn’t drink either, did we? Neither were we very good at cricket. Our team was made up of men from a thirties team, surprisingly enough past winners, plus a few inexperienced youths, keen as a knife blade who in later life were to enjoy considerable success at local level. But not now. Our first game was a complete mis-match. Dismissed with ease and little interest we went away humiliated to lick our wounds. The next season we felt even more helpless. One of the town’s businessmen who regarded himself as something of an entrepreneur decided to bend the rules by bringing an “out of town” specialist. This cricketer was an opening batsman from Wellingborough, a nearby town whose towering furnaces could be seen belching out orange smoke away to the south from the elevation of “The Rec.” This “cricketer” was “H.H. Johnstone.”, a man who towered above us on the cricket field like those nearby furnaces and his name is etched on my memory long after I have since forgotten the names of more recent players. I make no excuses for including his name in this book for he was simply a pawn in the businessman’s game of “winning at all costs.” I suspect too that there was some money being laid on the outcome of the Tournament. Innocent pawn though he may have been, H.H. Johnstone batted like a king. His name appeared with sickening regularity in the cricket reports of the Northamptonshire Evening Telegraph. He seemed to score runs with the ease of a Bradman, amassing them like a bee amasses honey, sweet and desirable, although his looks were more akin to W.G. Grace, thick set and heavy jowled, a ridiculous schoolboy hat, red, small and striped, perched on his large head. That he played in this Tournament may not have been the best decision of his life. Not that he failed. Indeed, he, like Bradman again, was painfully and predictably successful. He stroked the bowling all round the ground with a fiercesome strength and speed which none of us had ever encountered and which was quite frightening. The baying crowd was delighted in its bigotry. The “Chapel” team, self appointed guardians of Puritan morals, was being given a drubbing. And what of H.H. Johnstone’s part? He despatched our punt efforts to all corners of the ground with an air of apology, not unlike the apocryphal story of the headmaster administering corporal punishment to a recalcitrant schoolboy whilst declaring: “This is going to hurt me more than it hurts you.” Even at the recent end of my career as I clicked down the pavilion steps and onto the field of play I carried the picture of H.H. Johnstone with me. On that evening, however, I was put to the test. And failed. And failed again. For some reason not best known to me at the time or since I was put to field at cover point. The cover drive happened to be H.H. Johnstone’s favourite shot. I was laid bare, weighed in the balance and found wanting. Not only was it his favourite shot but he was able to execute it in the best Sensitive, insecure adolescence can rarely take criticism or advice however well intentioned it may be, least of all from one’s loved ones. I can point to that game however, as a precise turning point in my attitude to cricket. Whilst it did not have quite the same drama as Saul’s conversion on the road to In case one is accused of self-praise it is also polite to recall the dropped catch, the “sitter”, the “dolly” and the misfields, and the accompanying humiliation and knowing that “a few years ago I’d have swallowed that one up easily” Yet it was ever a delight to feel the sting of the ball in the hand, the grip of the fingers round the seam and the look of the disappointed batsman on his way back to the pavilion. And all because of your skills. A brilliant piece of fielding at Test, County or local level whisks the mind back immediately to the evening match in the early fifties when a schoolboy capped W.G. Grace – like figure tormented a teenager who missed everything that came his way and whose emotions were shredded by the baying crowd and who determined that it would never happen again. And so, for the awakening, for the inspiration, for the conversion, thank you, H.H. Johnstone - wherever you are - elevated alongside “Fatty” Rose. Praise indeed! With the inclusion of outsiders, however, the true spirit of the Tournament was lost forever like the mundane lives of the villagers of a bygone age. What was the Chapel to do about it? Standing on strong moral ground as it did, it was in a dilemma. Either it condemned the practice, a stance which would be seen as “bad sportsmanship” on the part of other teams, or it ignored it which would undermine the very moral fabric it represented. Entering the competition again meant another humiliating drubbing anyway? Its team was well below the standard of cricket required even in that minor tournament. Yet it did not want to disappoint the youngsters attached to the Chapel for they were already a diminishing number. It was difficult to see what possible solution there could be. When every avenue had been explored, every wavering of the rules had been teased out, the solution came form the most unlikely of quarters. It was in the guise of a young lady! A regular Chapel goer, she was being courted by a young man who lived in another local town. Of all the men to choose she had chosen a cricketer. Of all the towns he could have come from, it was Wellingborough, and he was a fearsome bowler of some repute, tall, left-handed and fast - and of all teams he could have played for it was the same team as H.H. Johnstone himself! We could not believe our luck! He must be good! Our belief in the power of prayer took a great step forward on that day. Various religious expressions from Sunday School came flooding to our minds. “God moves in a mysterious way his wonders to perform,” and “manna from heaven,” were most oft quoted. The more dreamy types thought of it as God looking down on that postage stamp of a square to take pity on us! A few minor queries about the young man’s inclusion made us a little uneasy. Could we justify him in our team with complete conviction? Of course we could! The answer was obvious. The young man came to Burton Latimer frequently now, he worshipped at the Chapel, - that was as good for the rules of the tournament as working in a local factory, - and he was going to marry a As if to heighten the drama and to tease out the emotions even more, of all the teams we were drawn to play against it was the businessman’s XI which was to be our adversary; - the team of H.H. Johnstone, and the previous year’s winner of the trophy. Now this would be a battle of the giants, we would challenge them at their own level and on their own terms. Perhaps we could even beat them. Our confidence knew no bounds. The great evening came and we were as tight as drumskins with excitement. The business man “manager” of our opponents, had been fussing unctiously around his team in the dressing room from very early on, biased and bigoted as he was, trying to ensure that his team would win, - an outcome of which there could be little doubt. It was a mark of his character, of his fear that there should be any doubt in his mind. Not long before the captains went out and tossed up, someone, could it possibly have been H.H. Johnstone? – whispered to him of our new team member. To say that the blood drained from the buisnessman’s bespectacled face like rainwater down one of the town’s gutters was something of an understatement. Clearly he had been informed that our new man played in the same team as his “Goliath”, and that he was good, -in fact, he was very, very good. As the unhappy businessman squirmed his way into our changing room he caught sight of our tall blond acquisition and nearly lost control of his bowels. And there was nothing he could do about it but gape speechlessly before trying to think quickly on his feet. I thought he was going to faint. By this time the umpires were on their way out to the square, the captains had tossed up and the crowd was expectant. The businessman could not cause a fuss for that would show himself to be unsporting. What was he to do? The vision of that precious Tournament Cup was beginning to fade from his mind and his triumphant acceptance of it was fast becoming a picture in his dreams. But he wasn’t going to be beaten. He had to save face. Like the worst kind of a fawning spaniel, nauseating and obsequious, he confided loudly in the ear of our Captain that although he didn’t approve of the inclusion of this man in our team, he would overlook it this time on the grounds of camaraderie. His hypocrisy knew no bounds. I thought I was going to vomit. A fitting climax to this story would have been a report on how we had won the game, of how H.H. Johnstone had been dismissed for nought by our new “find”, of how he had been reduced to the level of the rest of us and of how our new man had shattered the hopes of the insecure businessman. Alas, it was not to be. One man does not make a team. That we had been given a lifeline was quite sufficient for us. That we had disconcerted the businessman, even if only for a brief moment, satisfied our need of seeing injustice caught out. We couldn’t really ask for more. The nature of our defeat that evening was nowhere near the humiliating disaster of previous years, for we too had grown, matured and were beginning to improve our cricket skills. I am not ashamed to admit, however, that we took malicious pleasure in seeing the pious concern tinged with not a little fear, on the “manager’s” face the moment he discovered the presence of our “demon” bowler. It was the face of the fallible exposed. The following year we were just as keen to take part in the tournament and perhaps even more so because by now our physiques, our experience, our knowledge of the game, our temperaments and our skills were continuing to improve. This time we were not to be put to the sword by H.H. Johnstone. This time our opponents took a little longer to dismiss us but not without a little assistance, unfair and potent, from an umpire. Here was man’s fallibility again, - some might call it “cheating”. We could not believe that gamesmanship could happen again and deprive us of any success, - and in a game which was synonymous with fair play. But we were wrong. Unskilled in the school of life, ignorant of man’s puny need to assert himself over his opponents to save face, we entered the match with naïve optimism. Our opponents had a “star” bowler, proud as a male peacock displaying his own abilities he gave the impression of going through the motions, bored and disinterested, against another weak Chapel team which he knew he could humiliate. He knew his team would win, there was never a doubt in his mind. But this year things were a little different. We were not going to be rolled over as quickly as in earlier seasons. We would not go down without a struggle. We were quick, we had a good eye, and we were as keen as blades of grass. We were also optimistic. It had never entered the bowler’s mind that we could possibly show any ability at the game, that we could actually put bat to ball, that we could field and that some could bowl. He dismissed the very idea of any of us having nimble footwork. But we had read about Bradman and how his footwork was the secret of his phenomenal success. Everything on that evening was all too easy for the bowler in question. Put into bat we had lost some early wickets to him and, “to make a game of it” he was now bowling deliberate and slow, turning the ball from off to leg, still, however, posing us problems which none of us found easy to solve. But someone did. A fifteen year old, uninhibited and strong, who had scored a few runs off him already, took it upon himself to dance down the wicket, and swing his bat in a powerful arc across the line in true Bradman fashion. The ball was over the shining, upturned faces of the leering cronies on the boundary before the bowler had completed his follow through and on its way to the confines of the Jacobean Hall. To say the bowler was stunned would be an understatement. His onetime fickle supporters were now cheering the young batsman and jeering their erstwhile friend. It was an example of all that is best in childish fickleness. What could he do? It must not be allowed to happen again. Drastic action was called for to prevent this youth from humiliating him, to prevent this bunch of “no-hopers” from doing remotely well. What could he do? Suddenly the answer was as clear to him as the raucous cawing of the rooks in the encroaching spinney. The bowler’s mind moved deliberately into gear and he begun to have a casual and seemingly inconsequential chat with his friend, the umpire. They could have been talking about the weather or the price of bread. But we knew they weren’t. His pride had been pricked now and these whippersnappers were not going to ruin his bowling average. They had to be got rid of like a cow rids itself of irritating flies with a languid flick of the tail. It was not long before the problem was solved aided by the naivete of the young batsman who, with surging confidence, was going for speedy singles. On one such dash he was well past the wickets when a shout went up and the wickets were broken. The cry of “Owzat?” was just a bit of fun. The youthful batsman grinned as he turned to wait for the ball to be returned to the bowler. And saw the Umpire looking at him sheepishly with index finger held aloft. The batsman blinked, then gulped. “What me? Out? “The umpire nodded slowly and let out a false sigh. “Sorry, son. Just out!” “No? You’re joking!” In later life a sprinkling of colourful adjectives might have accompanied his enquiry. “I don’t believe it!” The batsman looked at the bowler who, shrugging his shoulders, was grinning in self-satisfaction to the crowd, and then looked at the umpire whose finger was still raised. He had no option but to trudge back to the pavilion, all hopes of turning the tables now dashed. As he passed the bowler he heard the insulting comment addressed to the umpire as much as to anyone else, “Course, he only had one shot!” The young batsman could have been forgiven an expletive but Chapel principles and strong self-discipline cloaked him and he was defeated. Defeated by cheating. He felt sick. Yet he knew he had triumphed having shown some blossoming cricket skill and having walked off the ground with dignity. It was not the first time he or any of us would experience such a flagrant disregard for rules but it was the most memorable in our lives at that time. It has been interesting to hear recent comments about poor umpiring decisions in test matches and that players are rightly censured for comments as to their suitability to engage in a five day Test Match. Such things are best left to the administrators who have other umpires to choose from should the need arise rather than see the curmudgeonly comments of the players. Even in today’s very different world cricket retains its air of fair play and correctness and occupies high moral ground - and long may it do so. In a career umpiring decisions even themselves out, it is only the exception which sticks in the mind. Such examples are best forgotten except perhaps in the telling of them for the amusement of friends, a temptation given into above and below. The above incident cemented itself in the mind because of the imbalance of the game. It was an empty gesture and served no purpose in influencing the outcome of the tournament one way or another. That was what was so irritating about it - even to an impressionable and naïve fifteen year old. But it did help towards cement the notion of fair play in cricket from its example of how the rules could be bent and how man can always be relied on to make and see an easy way out of a situation or make things appear better for himself. This simple example, with its negative overtones threw up in sharp contrast the self – respect cricket imbues in its players. That is why it is so good for any player and, indeed, for anyone who comes into contact with its standards. (Click here for 100 Years Centenary 1881-1981)

|

|||